It is a vehement approach to seeing the same drama on the stage I saw almost a decade ago. But Tuesday evening, I appeased myself with the title and context of the drama that instilled a second political thought while I was in active student politics and held all the aces to play my ace. There was no usherette to welcome me, but that evening at seven, the first bell was rung in the sheer cramming studio theatre; I started to imagine the whole Shilpakala Academy as Illyria—an actual country of classical antiquity where the play is set—a mare’s nest of my first experience with the piece The Political Murder performed by Bangladesh Udichi Shilpighosthi probably in 2011 or 2012. But on the spur of the moment, I realised dance could not be resumed, at least not to the same tune. Long periods—many theories go out of vogue, emotions are selling in the air, and considerable evidence has become a relic; but still, neither the awe-inspiring text of Jean-Paul Sartre and the literary translation of Arpita Ghosh nor the assiduous performance of Udichi’s artists, I took the plunge into a specific lacuna of deciphering the to-and-fro of the play.

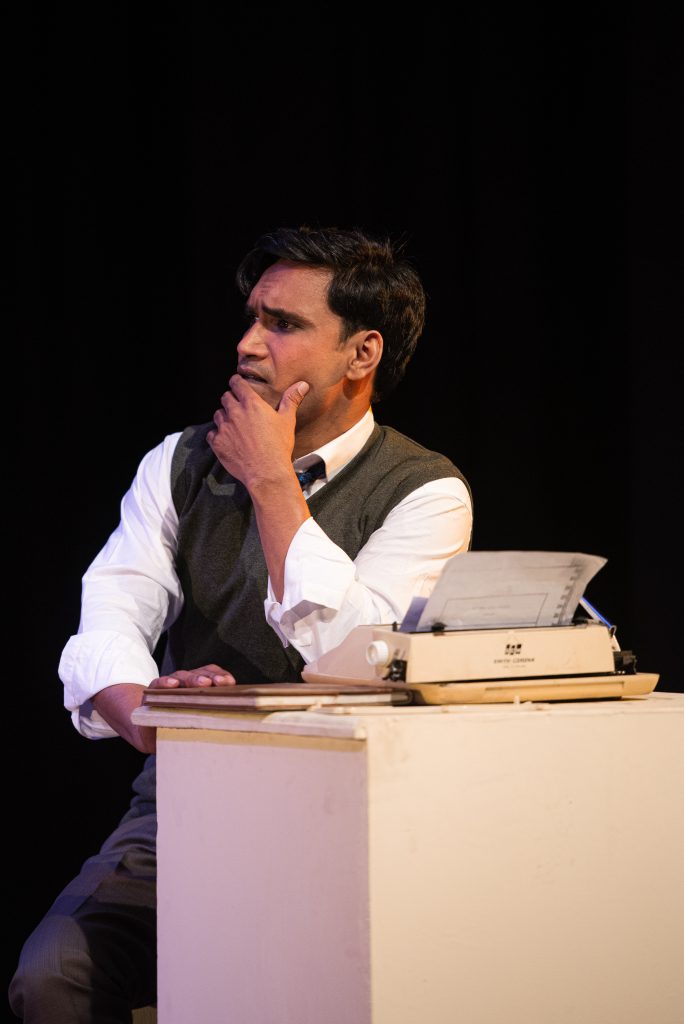

In 2006, I read the play in Sartre’s No Exit and Three Other Plays by Vintage International, where the seven-act play Les Mains sales is titled Dirty Hands; or it may say that I strode over the idea of conflicting right political action with profound morality. But that did not create any vantage point for me to cease the tension between politics and ethics—the central focus in Sartre’s play. During the Cold War’s ideological clash, the conflict between Hugo and Hoederer represented varying ethical standards based on different ideals. In his search for self-respect and truth, the young hero, Hugo, leaves his father’s house and joins the Communists of his Nazi-occupied country. As a prominent member of the Communist party, Hoederer proposes that the party collaborate with the Nationalist and Fascist parties to form a coalition government, allowing the Communist party to rise. While Hoederer seems compelled by his plan and sees its necessity, Hugo and other party members strongly disagree.

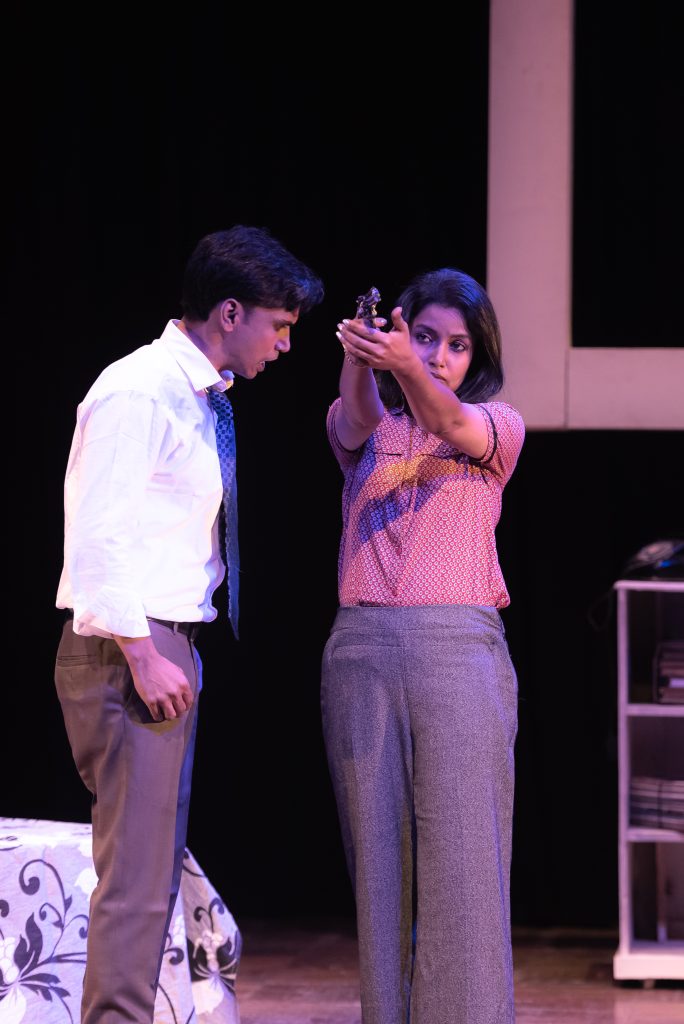

Another member orders Hugo to murder Hoederer to continue the party’s status and preserve the communist ideology. But flies of quandaries attack Hugo when he finds Hoederer a fascinating figure, and his particular démarche turns into remissness. Hugo does, however, make a decision. In the meantime, the party decides that Hoederer is not a traitor but a hero—leaving Hugo as a man alone. The irony of the end reflects upon the party, not upon Hoederer. His brand of opportunism was never effectively contradicted. Sartre condemns the party but not the Communists.

While The Political Murder was performed on the stage, the text and time of the play, apt with the evade and entente in politics, swayed upon me rather than the performance. But I repeat my aforementioned statement that the performance was alluring. It may be worthwhile to say this is high time to disembody the connotation of Sartre’s text and delineate it in the current world as the bedrock of today’s political thoughts (whatever the ism) is in the fray, and every day the political being is facing the bizarre political situations. So, the 1948 drama Dirty Hands (or The political Murder) would be reinterpreted by a theoretical embellishment that is all ears of today’s longing. Don’t we live in a world of ideological clashes? Ain’t we playing the game of brinkmanship?

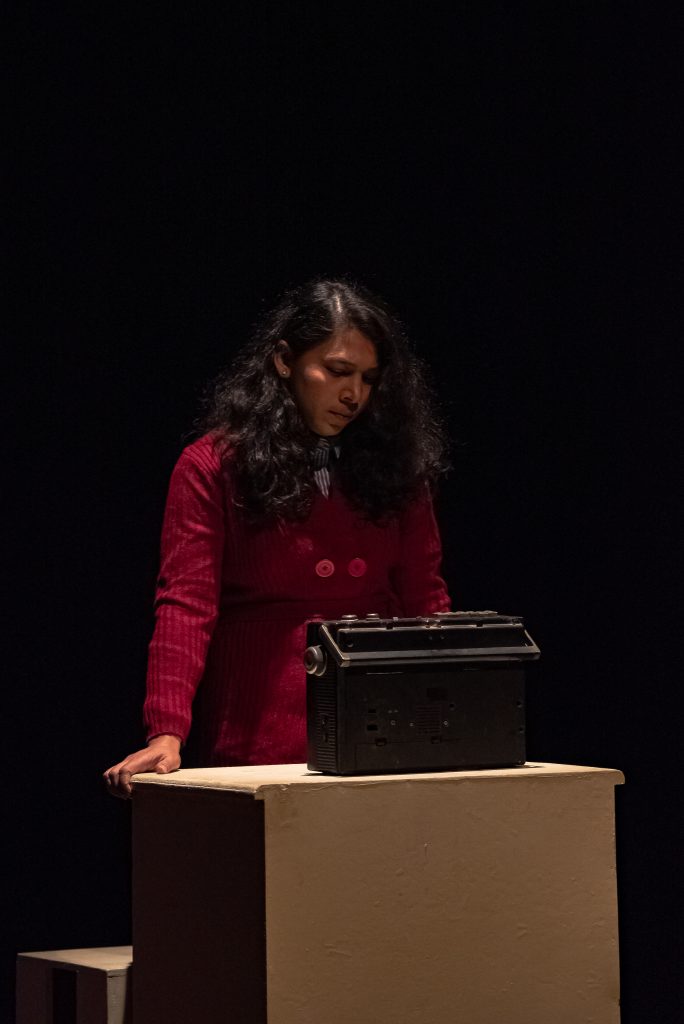

Legions are worming by the delusions of digital deity. Nowadays, Hoederer is a Facebook motivational speaker, Hugo Barine is busy with intellectual tweeting, and Jessica increases her Instagram followers by posting comely photos. Louis and Olga wine and dine the left and right simultaneously. Schadenfreude has become some political parties’ lovely hobby. So, a de novo text design for this play is waiting in the wings to resolve some questions. Does the overriding of moral constraints occur within morality or somehow beyond it? Is it restricted only to politics? Is the plot the same as in other areas of our life? In a politicised system, how do the citizens share the responsibility for a political murder?

I am privileged to know the play’s director Ratan Deb and almost all the artists. Their immaculate concept of staging and Ratan Da’s exquisite taste for art ushered me to the questions mentioned above. To me, there is no upshot for art; in any form, every art is just a continuation of its erstwhile. There are neither cast-iron narratives nor counter-narratives. Dirty hands are still in the world, and political murder too, so as an audience, I am eagerly waiting for Ratan Da’s audacious attempt to kindle Sartre’s text with the aura of modern times.